Planetary Radio • Jan 14, 2026

IMAP and the shape of the heliosphere

On This Episode

David McComas

Professor of Astrophysical Sciences, Princeton University; Principal Investigator, NASA’s IMAP and IBEX missions

Matina Gkioulidou

Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory; IMAP Project Scientist and Co-Investigator

Sarah Al-Ahmed

Planetary Radio Host and Producer for The Planetary Society

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

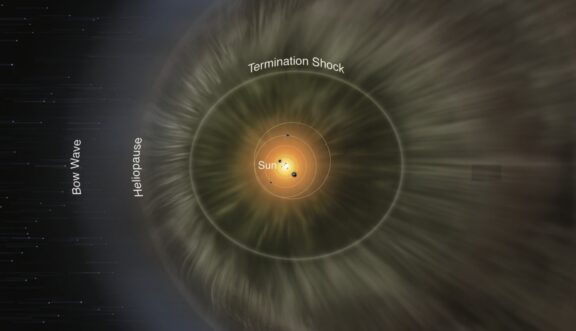

Our Solar System is wrapped in a vast, invisible bubble created by the Sun, a protective region that shields Earth and the planets from much of the radiation that fills our galaxy. But until recently, scientists have only had rough sketches of what this boundary looks like and how it behaves.

In this episode of Planetary Radio, host Sarah Al-Ahmed is joined by David McComas, professor of astrophysical sciences at Princeton University and principal investigator of NASA’s Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe (IMAP) and Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX) missions, along with Matina Gkioulidou, a heliophysicist at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, former IMAP-Ultra instrument lead, and current IMAP project scientist and co-investigator.

Now stationed at the Sun–Earth L1 Lagrange point, IMAP uses 10 instruments to study the heliosphere — the region where the solar wind collides with material from interstellar space. The mission does this by tracking energetic neutral atoms, particles that travel in straight lines from distant regions of the heliosphere, allowing scientists to map areas of space that spacecraft can’t directly sample.

McComas and Gkioulidou explain how IMAP builds on the legacy of Interstellar Boundary Explorer, what makes this mission different, and why understanding the Sun’s influence across space matters not just for fundamental science, but for space-weather forecasting and protecting technology and astronauts closer to home.

Related Links

- IMAP

- IMAP Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Interstellar Boundary Explorer

- Planetary Radio: Voyager and the heliopause: Exploring where the Sun gives way to the stars

- A Million Miles Away

- David J. McComas, Ph.D. | Space Physics at Princeton

- Matina Gkioulidou | Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory

- IMAP (Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe) Archives

- The Quest to Find the Edge of the Solar System

- Princeton-led IMAP Mission Launches Into Deep Space

- Princeton in space: IMAP prepares for launch

- NASA, NOAA Launch Three Spacecraft to Map Sun’s Influence Across Space

- NASA Launches IMAP Mission to Study the Heliosphere and Better Understand Space Weather

- Buy a Planetary Radio T-Shirt

- The Planetary Society shop

- The Night Sky

- The Downlink

Transcript

Sarah Al-Ahmed:

Meet IMAP this week on Planetary Radio. I'm Sarah Al-Ahmed of The Planetary Society, with more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond.

A vast and invisible bubble surrounds our sun and planets, shielding us from much of the radiation that fills the galaxy. It's called the heliosphere, and for decades, we've only had a rough understanding of what it looks like, how it moves, and how it protects us. Now, a new mission is helping to change that. NASA's Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe, or IMAP, is a space mission designed to map the outer boundary of the heliosphere and study how particles are energized as our sun interacts with interstellar space, all from a vantage point that's about a million miles from earth.

This week, I'm joined by David McComas, Professor of Astrophysical Sciences at Princeton University, and Principal Investigator of NASA's IMAP and IBEX missions. Along with Matina Gkioulidou, a Heliophysicist at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, former IMAP-Ultra Instrument Lead, and current IMAP Project Scientist and Co-investigator. Together, we'll talk about how IMAP uses its 10 instruments to turn tiny particles into a global picture of our solar system's protective shield. After the interview, we'll check in with Bruce Betts, our Chief Scientist for What's Up.

If you love Planetary Radio and want to stay informed about the latest space discoveries, make sure you hit that subscribe button on your favorite podcasting platform. By subscribing, you'll never miss an episode filled with new and awe-inspiring ways to know the cosmos and our place within it.

On September 24th, 2025, NASA launched a new mission designed to map one of the most important and least visible features of our solar system, the Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe, or IMAP, is now stationed about a million miles from earth at the Sun-Earth L1 Lagrange point, where it can maintain a constant, uninterrupted view of the space shaped by our sun. From this vantage point, IMAP studies the heliosphere. That's the enormous bubble inflated by the solar wind that surrounds our entire solar system and helps shield us from high energy radiation coming in from the rest of the galaxy.

Mapping something this vast and invisible requires a clever trick, though. IMAP does it by detecting energetic neutral atoms, or ENAs. Those are particles that form when fast moving charged particles from our solar wind collide with neutral atoms drifting in from interstellar space. In those encounters, the particles essentially swap rolls. The charged solar wind particles steal an electron and become neutral, while the previously neutral interstellar atoms become charged. Once that happens, the newly neutral particles are no longer guided by magnetic fields. That allows them to travel in straight lines and carry information back to us from the distant parts of the heliosphere that spacecraft can't directly sample. By collecting and measuring energetic neutral atoms, IMAP can build a global map of the heliosphere and investigate how particles are accelerated to extreme energies out there at the boundary between our heliosphere and interstellar space.

IMAP builds on a legacy of earlier emissions, including the Interstellar Boundary Explorer, or IBEX. It was launched back in 2008, and produced the first all sky maps of the heliosphere using energetic neutral atoms. IBEX revealed that the boundary of our solar system is far more complex than we expected, including the discovery of a mysterious ribbon-like structure encircling the heliosphere. IMAP takes the next step after IBEX, with 10 advanced instruments working together to deliver higher resolution, greater sensitivity, and continuous monitoring of space weather near our earth.

To help us understand how all of this works, I'm joined by Dr. David McComas, Professor of Astrophysical Sciences at Princeton University, and Principal Investigator of NASA's IMAP and IBEX missions. Along with Dr. Matina Gkioulidou, a Heliophysicist at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, former IMAP-Ultra Instrument Lead, and current IMAP Project Scientist and Co-investigator.

Hey, thanks for joining me.

David McComas: Hey, it's great to be here.

Matina Gkioulidou: Yeah, thank you for having us.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, first of all, I wanted to say congratulations on the launch back in September.

David McComas: Well, thanks so much. It was spectacular, wasn't it? Did you get to see it?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I watched the live stream, but I didn't get to see it in person.

David McComas: Yeah, there's a two-minute video online that's just awesome. Goes all the way through the separation of the spinning spacecraft and everything.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's so cool.

Matina Gkioulidou: Yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I mean, after years of development, what was it like finally seeing IMAP riding into orbit on a Falcon nine?

Matina Gkioulidou: I burst into tears, actually.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I would too.

Matina Gkioulidou: Happy tears, but yeah, it was very, very emotional for me. And every time I see the video again, I get the goosebumps now. It was amazing.

David McComas: And for me, I was still just holding my breath because I know that the first couple of minutes after you launch is when almost all the danger to the mission is. You spent eight years building the spacecraft and the instruments and doing all this really hard work. You put it on top of this big rocket and it shakes in and there's acceleration and all kinds of other stuff. And so, it's usually a few minutes after the launch that I actually let my breath out and relax a little bit.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah. I can't even imagine that feeling of just finally trying to let yourself let go of that stress after all that time.

David McComas: Yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, just last week, I shared my conversation with Linda Spilker, who's the Project Scientist for Voyager, and we spoke about what Voyager's taught us about the heliopause and the broader structure of the heliosphere. And she mentioned just how excited she is to actually see the results from IMAP, because I think it's going to inform so many of the mysteries that began with Voyager's journey out there.

David McComas: Yeah, absolutely. And in fact, it's fascinating that we still have the Voyager is operating, at least for a while longer. It'll be taking images of the outer heliosphere and the interaction with the very local interstellar medium, while we're actually making measurements out there at the same time.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, it'll be really interesting to see, I mean, depending on how long the spacecraft survive, what kind of information we can get near where we are, and then how that corresponds to what Voyager is experiencing out there. Even though it is now past the heliopause and out into interstellar space, but there's still a lot that we can learn there.

David McComas: Yeah, that's fascinating too, and IMAP also measures things from interstellar space. There are interstellar neutrals floating in from interstellar space, about 26 kilometers per second. We measure those very precisely with one of our instruments, the composition. We also measure interstellar dust, which comes in from outside and the rest of the galaxy and comes into the heliosphere when we measure that directly at particle by particle, dust grain by dust grain.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: There's so much that we don't know about this, I'm really glad that we're going to find more ways to explore it. Not that we haven't before, but just the opening of resolution here, it's so much more precise than we've seen in previous missions. And there's so many things we don't understand, so we'll unpack a little bit of that. But before we dig deeper, there's a lot of things that this mission is going to try to accomplish. So, can you speak a little bit about the main mission objectives?

Matina Gkioulidou: First of all, IMAP is the mission that is set. We are out there, we want to explore our heliosphere. Right? So there's bubble that surrounds our solar system and protects us from galactic radiation. But IMAP is very unique in a sense that we explore this heliosphere all the way from very close to the earth, about a million miles away from the earth, we take measurements, and we try to combine those measurements with what we see coming from 10 billion miles away from us. So, we want to explore the heliosphere as a whole, that's the unique of that mission. Before, we either had missions taking measurements from out there or measurements from close to us. Now, we combine these two pieces of the puzzle together.

David McComas: Yeah, I like to call it integrative science. We've had IBEX and things taking ENA measurements of the outer heliosphere in lower resolution than IMAP will do. We've had a bunch of in situ measurements of particle acceleration closer to the sun, but we're trying very intentionally not just to have the measurements of these 10 instruments, but to use them in a new way together so that we're actually discovering how these integrate together and how particle acceleration in the outer heliosphere is informed of a particle acceleration in the inner heliosphere.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's a really large system to try to understand as a whole. So, it's very complex and really important to have so many different instruments to monitor it. But this spacecraft is traveling, currently it's on its way to the Earth-Sun L1 Lagrange Point. That's about a million miles away from Earth, as you said. Why is that such an ideal location for us to try to understand this larger system?

David McComas: Well, first of all, it's a very good, stable place to go and orbit about, it takes very little fuel to stay in an orbit around that. It's also upstream of the earth, about a million miles, so that space weather events that are going to affect the earth arrive there first, typically 30 or 40 minutes before they arrive at earth, and so it's a good outpost for that. It's also a place that's far enough away from the backgrounds which are produced by the earth. The earth has a lot of energetic particles of its own, it emits its own energetic neutral atoms. And so it actually, one of the main limitations for IBEX, the precursor to IMAP, is the fact that it's an Earth orbit and that it has these enhanced backgrounds because of being in the Earth's magnetosphere most of the time. So, IMAP by going to L1 has a lot of advantages and they all work together for both doing our in situ science and our space weather science, and also for the observations of the outer heliosphere.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, it takes about three and a half months for the spacecraft to go from launch to actually reaching its halo orbit around L1. So as people are listening to this conversation, I think the spacecraft will have just about arrived there. What kind of science and calibrations are you doing while it's in its cruise phase?

Matina Gkioulidou: Yes. So we right now, actually, since we launched and all the way through January, we are going through the period that is called commissioning. So we have turned our instruments one by one. Everything is working great, by the way, so far, so we are very happy about it. And we are taking careful measurements, both on engineering mode and science mode, to make sure all our measurements is what we expect them to be. And as you said, yes, we go through the process where we are tuning our instruments, right? We are fine-tuning them so that we can get the best science. We go through these calibration periods, we are changing parameters, and by February 1st, when we start our phase E, we should have just science mode data, and the data will be publicly available months after that.

David McComas: After a validation period, where the science team is able to make sure that we've got everything properly culled and calibrated and that it's correct for the world to use, yes.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, I think many people understand why it's important to understand local space weather, right? What's going on with the sun can deeply impact our technologically driven society. But fewer people I think, understand why it's so important for us to understand this larger system in which we live. So, why is mapping the heliosphere so crucial for us to understand the habitability of our solar system, and even further out, the habitability of exoplanetary systems?

David McComas:

Yeah, so the largest limitation on human exploration outside of the Earth's magnetosphere is the galactic cosmic radiation. If you have a solar flare or a space weather event, you can get your astronauts underground if they're on the moon or you can get them into the central part of the space station or something for a brief period of time, but they can't live in those places. You have to be able to get out and move around. Galactic cosmic radiation is there all the time, and so the main shield for the galactic cosmic radiation is the outer heliosphere. About 90% of the 100 MeV or million electron volts, which is a typical galactic cosmic ray energy, about 90% of those are shielded out by the outer heliosphere in this interaction between the heliosphere and the very local interstellar median. That's the region that we're studying directly. If that varies over time, and it does, it varies over the solar cycle, but it could also vary over longer times, that could have very important implications for whether or not we really can send people to Mars or have them live outside longer periods of time.

It's also interesting from a broader perspective of, extra solar planets around other stars and what is needed to have habitability in those. If there's too much external radiation, it's probably a non-starter for life. It may be that some level of radiation is actually good for evolution because it mixes up the DNA, but we all know that too much radiation is not good for life.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, there's probably some kind of Goldilocks zone there for perfect evolution of life, but it's so far beyond what we know yet. So yeah, this is a first beginning context.

David McComas: Yeah, I think we're probably in the Goldilocks zone for that also. If it was 10 times higher, I think the sort of life that we know would be very hard to maintain, and maybe there'd be something else, I have no idea, but the protection of the heliosphere is very important for human exploration.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, there's a lot we don't understand about what kinds of stars are just baking their planets in radiation, but also just how the larger system is impacting these. I'd be really curious to know more about the heliosphere around different types of stars, but we have to understand our own star first in order to even begin to figure that out.

David McComas: Although we do have some beautiful pictures of those. They're called astrospheres, and some of them are actually able to, there are such strong interactions because of high densities and high speeds that they're actually able to heat the plasma and they emit light. And so, we see them in visible light, sometimes in UV, sometimes in infrared. But our own situation is not that way, the interaction is not so strong that it emits this light. And so, we've had to invent a whole new type of astronomy that we call energetic neutral atom or ENA astronomy, which allows us to make observations of this interaction region at the edge of our heliosphere through individual atoms, which charge exchange out there and carry the information of what the plasma is like out there, all the way back in past the planets and all the way into our spacecraft at L1, and allows us to remotely image this interaction region, not using light, but using the atoms themselves.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Can you talk a little bit about that charge exchange process?

David McComas:

There's cold interstellar material that floats into the heliosphere. The interstellar medium's about 50% ionized and 50% neutral. In the ionized part, the charged particle charge protons, mostly. They can't get into the heliosphere because it's a magnetized plasma and they're tied to the magnetic fields that they're on, which are outside the heliosphere. But the neutrals aren't bound to the magnetic field because they have no charge to them, and so they come floating in across the heliopause, the outer boundary of the heliosphere.

And sometimes they charge exchange where an electron will jump between them and a proton that's out there, and the proton that's out there in the plasma in the outer heliosphere becomes neutralized and it keeps going whatever direction is was going at exactly the instance of neutralization. So, it's gyrating around the magnetic field, it's flowing with the flow, and all of a sudden there's this charge exchange and it just goes zipping off tangentially in exactly the direction that it was going. And almost all of those go off in crazy directions and nobody ever sees them, but a tiny fraction of them going in exactly the right direction that they come all the way back into L1, where we're able to observe them.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: So it takes quite a while for these to travel from out there all the way in here.

David McComas: Well, it depends on their energy. If they're a keV, 1,000 electron volts, which is a typical solar wind energy, they travel 100 AU, the distance from the boundary roughly, back into one AU in about a year.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, that's not bad. Well, in my conversation last week about the heliopause, we spoke a bit about the global structure of the heliosphere, and there are so many different mysteries that we're still trying to piece together about whether or not it has this comet-like tail or whether or not it's more croissant-shaped or spherical, or even how solar activity influences this kind of thing and how the magnetic field matches up with the magnetic field outside that boundary. So, which of these structural mysteries do you think IMAP is positioned to help us resolve first?

David McComas:

I don't personally think that the shape of the heliosphere is really a big issue. I know a lot has been made of that, but I don't actually think that that's a very important question. I think we don't understand a lot of the actual physics and interaction in the outer boundary of the heliosphere, and I think we're going to be much better at doing that.

We have had imaging from about 500 eV to six keV for now 17 years, and we've learned a huge amount from that. But now, we're in the process of starting to collect observations of these ENAs down from about 10 electron volts up to over 100 kilo electron volts. So, it's a factor of 10,000. So, as opposed to a factor of 10, it's a factor of 10,000 in energy. And we've got overlap between the low and high ENA imagers and between the high and the ultra-high ENA imagers, and we have good cross calibration between those, and so we're going to be able to do the entire energy spectrum and understand in detail what the physical processes that are going on in the outer boundaries are. I think those are the really exciting questions.

Matina Gkioulidou: Yeah, and if I can add to that, the huge energy range is the better spacial resolution of these measurements. And I will say, because we have two of each cameras, at least for the two ENA images, we have more collecting power so we can get more of those particles faster. So we will be able to find, I think, very interesting temporal changes that IBEX was not able to address. But for me, all these new data we have that are much better quality, I'm very excited to see the new stuff that we didn't even expect. New discoveries that, who knows what we might find.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Particle acceleration is one of the biggest questions in heliophysics right now, and I think the problem is twofold. One, why are these particles near the sun being accelerated? And two, why are these particles out near the boundary between the heliosphere and interstellar space being accelerated? And overall, what makes this such a challenging thing to study?

Matina Gkioulidou:

Yes. So, particle acceleration is a process that helio, it's at the center of one of the major scientific questions. And it's challenging because it takes a lot of measurements happening all at the same time from different instruments. So, that's exactly what IMAP has.

For example, we have the ENA images measuring stuff from remotely, and they cover all that energy so they can address acceleration processes out there at the boundaries of our solar system. But we have another five instruments that take measurements as we say in situ locally at L1. So, these are the instruments that measure the stuff that come directly from the sun right before they hit the earth. Right? And those instruments also cover a very wide energy range from qEV, all thermal solar wind particles, all the way to very high energy particles, solar energetic protons, and things that are dangerous for, as we said earlier, technological assets that we have in the space around Earth, or our astronauts as they try to get out of the safe space around Earth and go explore other planets. So, it's very important to have these measurements.

And in fact, with IMAP, we also have the architecture that we call I-ALiRT. It's an architecture we put together so that we broadcast 24/7 what we say near real-time space weather data. So, all these dangerous particles, high energy particles, solar wind, magnetic field, they're being broadcasted, and all we need is ground stations around the world to receive those data. And once they receive them, within five minutes, they're available for everybody to look at once we release, we go into that phase of our mission. So right now, we have few stations around the world, so there are some gaps in that I-ALiRT architecture, but we hope to cover the whole globe soon enough. And that means that you get information about these acceleration processes as they happen and right before they hit the earth.

David McComas: Particle acceleration's not a single thing. Magnetic reconnection, when magnetic fields merge, accelerates particles, shocks and plasmas accelerate particles, turbulence can accelerate particles. There are a whole bunch of different physical processes that in different situations and locations, one or another, or several of them are more or less important than the others. But particle acceleration happens a lot and it has important consequences because of the radiation effects and all of that sort of thing. And so, it's really a very complicated system to try to suss out which type of acceleration's happening where, why, and under what conditions, and how even sometimes one plays with another one. You get some acceleration out of a magnetic reconnection, and then a shock comes through and accelerates the particles even further. So, it's a very complicated thing from a physics perspective, but it's also very important.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, if we look at what we've been learning about particle acceleration near the sun with things like Parker Solar Probe and Solar Orbiter, we've made some good inroads there. So, what have we learned so far about the different mechanisms that are accelerating those particles, and what can IMAP expand on in that area?

David McComas:

Well, one thing for sure that IMAP does that those don't do, they're great missions and we have been discovering a lot of really interesting things about in situ particle acceleration near the sun. But there's no connection to the further acceleration in the outer heliosphere, the acceleration of anomalous cosmic rays, acceleration at the termination shock, things like that. IMAP's really the mission to put together the pieces. Again, it's this integrative science where it's not just studying this one interesting physics problem here locally or that one there locally in the magnetosphere or solar corona or whatever, but being able to piece together those parts all the way out across the entire realm of our solar system, basically, or our heliosphere, which is the region of space that's dominated by our sun.

And so, that integration's a really important aspect of IMAP and we're so dedicated to that that we, unlike any other prior mission, don't really center our analysis around separate instruments. The separate instruments take data because that's the way you take data, but we've built an infrastructure along with the instruments to allow us to immediately have the combined data to work with. So, my goal is that we'll never be publishing individual instrument papers, here's what we see in electrons, here we see in this energy of ions. But instead, we'll be talking about fundamental physics processes that pull in two or three or five, however many instruments have relevant data to it, in a seamless way that we're able to do very quickly and easily in IMAP.

Matina Gkioulidou: This connection between acceleration processes at L1 and all the way out there, the IBEX mission actually did find the connection of when you have high solar wind activity, you see the effects in the outer heliosphere with some delay in years, like a couple of years later after particles have gone out and come back to US ENAs. But IBEX had just got remote sensing and they were counting on other missions to have some measurements of the solar wind locally. IMAP has both, so all the energies we're talking about from in situ and remotely, they cover all the ranges. So whatever we are measuring at L1, with some delay, we're going to see it coming back to us. So, if something doesn't look consistent between these two, maybe something is happening in the outer heliosphere we hadn't thought about in terms of acceleration process, for example. These are the things we are trying to address, and they're quite unique in this mission.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Plus, IMAP has something like a 38 times resolution, I think, in its global map versus IBEX. So, there's so much more we might be able to see there. Are there things that you wish you could have seen with IBEX but were just impossible, given its limited capacity compared to IMAP?

David McComas:

Well, yes, but we don't know what they are because we didn't get there, but we're already starting to see some hints of those even in the very earliest data from IMAP. It's very clear that the backgrounds are much lower as we get to L1, and because of all the improvements we made between IBEX and IMAP in the instrument design and capabilities. They described already how these individual energetic neutral atoms have to be on this just perfect trajectory to make their way all the way back into L1 and get observed, come into the aperture of one of these instruments. Som our signal is extremely low, and so a lot of the game in energetic neutral atom astronomy is pushing the backgrounds down.

In the end, what you're able to do from a physics perspective is a ratio, it's a function of this signal-to-noise. Signal-to-noise and ENA imaging on IBEX is often a decade. And if you can push down the background another decade or two decades, there's a whole bunch of other signal under there that we've never seen. It's like having a cloud bank in a bunch of mountains. If the cloud bank goes down, more and more of the peaks come out, and the lower the cloud banks goes, the more you see the mountain range and you can understand what's there. And so with IBEX, we're just seeing that the peaks of the very tallest mountains, and now with IMAP, we're able to push those backgrounds down and really see the mountain ranges themselves.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I think one of the biggest mysteries to come out of the IBEX mission that I'm still thinking about is this energetic neutral atom ribbon thing.

David McComas: Oh, yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And it was a structure that no one predicted until you went to look for it. Can you talk a little bit about what that mystery was?

David McComas:

Yeah, I'd be happy to. So, this is what experimentalists live for, is finding stuff that no theorist has ever thought about. No theorist has ever had a model or a theory. It's great to find things that people have posed and suggested and theorized about in advance, but when you go out and find new physical phenomena that nobody ever thought about, as an experimentalist, that's like, that's the day. So, that's the day it was with IBEX as we started to see this structure, which is basically a circle, a ring of enhanced emissions that is coming in from directions where the magnetic field in the very local interstellar medium is perpendicular to our line of sight. It's just basically a radial line of sight. And so, where the field is exactly perpendicular to a radial line of sight is where you get the strongest emission.

And so within a couple years, and we didn't know why in the original science paper that I led, we had six suggestions in there, what might produce that, but we didn't really know. Within a couple of years, the theorists had been catching up with us and there were 13 proposed different ways that you could produce the ribbon, and they were vastly different from things close in to very far out, well outside the heliosphere. And so, there was a process of simultaneously taking more data, making better measurements over time, getting better statistics, that sort of thing, and doing the experimental tests, and the theory folks working on the other side.

And now, I think we've resolved that the ribbon comes from a process we call secondary ENA emission, in which solar wind and some of those material in the heliosheath produces neutrals that go out beyond the heliopause into the very local interstellar medium, and they get re-ionized there, they gyrate around the magnetic field there locally, typically takes two years before they become neutralized yet again a second time, which is why it's secondary ENAs. With that secondary neutralization, some fraction of them come back in and get observed.

And so now what we're arguing about is the detailed plasma physics and the very local interstellar medium. Do they come preferentially back in radially because they've stayed in a distribution, which is like a donut which is perpendicular to the magnetic field, or is it because the physics of the process of picking those up actually creates a region with a higher density? And so, we're doing detailed plasma physics on the plasma 100 to 200 AU away through this ENA signal. And so, it's really fascinating how deeply we've been able to get into that plasma physics, and now the arguments that we have are very subtle about what's going on out there. Now we're going to get a whole new round of observations from IMAP over a broader energy range, which much better sensitivity and resolution, and we'll really be able to dissect these different theories and ideas about the plasma physics and probably get to the very bottom of exactly how the ribbon works.

Matina Gkioulidou: Yeah, it's always great to hear Dave talking about the ribbon because he gets so excited. I love it. But the other thing I wanted to say is that, and Dave, correct me if I'm wrong, it's not just the theories that miss the ribbon in any of their theories. I think that, and I see that the figure from the science paper maybe, even the Voyagers, the local ones miss the ribbon.

David McComas: Oh, yeah.

Matina Gkioulidou: And I think that's the power of ENA imaging, right?

David McComas: Yeah.

Matina Gkioulidou: We don't take measurements locally there to get all the details, but we get the whole picture of the sky. So this structure showed up where locally the two Voyagers didn't capture it. Their locations were not at the right spot. So, I think that's another addition to the power of ENA imaging and ENA astronomy.

David McComas: Yeah. Actually, I like to use the analogy of the difference between a biopsy and an MRI. You can take a biopsy of a point or two if you want some really detailed information about the cells in that region. But if you want to understand how the whole organ is, you need to do something like an MRI where you can get all the different layers and all the different directions and all of that. And so, ENA imaging is very much the MRI of our heliosphere.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We'll be right back with the rest of my interview with David McComas and Matina Gkioulidou after the short break.

LeVar Burton:

Hi, y'all. LeVar Burton here. Through my roles on Star Trek and Reading Rainbow, I have seen generations of curious minds inspired by the strange new worlds explored in books and on television. I know how important it is to encourage that curiosity in a young explorer's life.

That's why I'm excited to share with you a new program from my friends at The Planetary Society. It's called The Planetary Academy, and anyone can join. Designed for ages five through nine by Bill Nye and the curriculum experts at The Planetary Society, The Planetary Academy is a special membership subscription for kids and families who love space. Members get quarterly mailed packages that take them on learning adventures through the many worlds of our solar system and beyond. Each package includes images and factoids, hands-on activities, experiments and games, and special surprises. A lifelong passion for space, science, and discovery starts when we're young. Give the gift of the cosmos to the explorer in your life.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, Matina, you are the Instrument Lead on IMAP-Ultra, which is one of the three energetic neutral atom cameras that are on board. But what makes specifically those high energy ENA measurements so essential?

Matina Gkioulidou:

So, let me slightly correct you. I'm not the instrument lead anymore. Since I became the project scientist, I passed the baton. George Clark is the Instrument Lead. Yes, I was the instrument lead during the development until a year ago or so.

So Ultra, it's the one instrument that IBEX didn't have. It's the one that captures the higher energies of those ENAs from 5 keV all the way to the hundreds of keVs. So, IBEX went up to six keV, now we have the overlap between IMAP high IMAP-Ultra, between five and 15 keV. And then Ultra picks it up all the way to hundreds of keVs. So, I think this is the... I am particularly excited by that population, the high energies that were never measured before. Of course, the signal-to-noise ratio that Dave talked about before is very challenging at those energies, because as you go to higher energies, the signal plummets, so you really need to bring your backgrounds even further down to capture that signal. But we get some encouraging images already. I think that this is going to be one of the discovery signs we can address with IMAP because the higher the energies we go, the deeper we can probe the heliosphere. Those energies can, it's easier for them to come all the way to us.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I read too, that IMAP spins at about four RPM, right? Clearly you got to have to spin the spacecraft in order to see most of the sky, but is there a reason for that specific rotation rate?

David McComas: It's actually the same rotation rate as IBEX. It's a trade space between in stabilizing the spacecraft and how quickly you need to scan voltages and things in order to get the energy coverage. And when you do the kind of detailed trade between those two, you typically end up with a number between two and five or something like that. We settled on four because we've been flying IBEX for years at four and very successfully, it seemed like there were a lot of advantages with staying with something that we knew. So it's not a magic number, but something within a factor or two of that is the right part of the trade space.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And you mentioned this a bit earlier, that it's not just studying energetic particles, it's sampling interstellar dust and neutrals that are flowing in from outside of the heliosphere. What are these grains and atoms able to tell us about the galaxy around us?

David McComas:

Well, I would say for the dust, we don't know yet because we've not seen much interstellar dust. The whole catalog of human measurements of interstellar dust is a number that we expect to exceed in the first year of IMAP measurements. And so, it's just a population that hasn't been well sampled. We can actually get the composition information from it because the dust grains break up in the instrument and we're able to separately measure what it's made of so we get the size of it, the speed of it, and then most importantly, the compositional information about it.

So, once we've been able to sample 100 or hundreds of these dust grains, we'll have a really good understanding of, is it one population or are there multiple populations? I mean, these are broken up planets, for example. This dust comes from planets that existed somewhere else, and then the star blew up and you ended up with all this debris coming out. And are you going to see a bunch of different families and populations of dust, or are you going to find that interstate dust is mostly one thing? So, there's a lot there we don't understand just because it's never been observed. There's a lot of discovery science that we'll for sure get from that.

On the direct interstellar neutrals, we've been measuring those with a low energy instrument on IBEX for 17 years now, and we've made a lot of good progress on it. But again, we're limited in our sensitivity. For example, we've tried very hard to get the deuterium ratio, hydrogen to deuterium ratio, which is a really important ratio. Isotopic ratio for understanding Big Bang Theory and stellar evolution and things like that. We've only been able to set some bounds on it with IBEX, but we should have the sensitivity with IMAP to actually get that ratio and a number of other isotopic ratios. And so, really much more precise measurements of the interstellar material tells us about the galaxy in general and the local part of the galaxy in particular.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I wanted to come back to something you mentioned earlier, the I-ALiRT system. You said it gives about a 30-minute or so warning, but what can we do with 30 minutes on Earth that would make a meaningful difference if we're interacting with some really intense solar weather?

Matina Gkioulidou: I think 30 to 45 minutes is actually good time to warn the systems and make sure either, I don't know what the mitigation would be, turn off certain spacecraft or-

David McComas:

Well, so for example, for the ground system, one of the things that it affects is, the power grid can break because you induce currents when you have these geomagnetic storms. And the power grid's actually able to break into smaller pieces. It's less efficient, so most of the time they run very long continuous lines, but they're able at certain points to break the grid apart so that there's not such a large current buildup. And so, they actively do that if they get good enough predictions.

Satellites can do some things to make themselves somewhat safer. You can certainly know in advance that if you see something really bad happening on your spacecraft, that it may just be this space weather event. I mean, if you're a defense satellite and you're looking for transient phenomena, it's good to know whether there's some environmental thing that might be happening at that time. So, there are a lot of things that you can do, and if you've got astronauts out on an EVA, you bring them in.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah.

Matina Gkioulidou: Oh yeah, definitely. Yeah, that's a good enough time to bring them in, yes.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I know, right? We need to worry about that so much, not just for our people on the ISS, but especially as we're moving forward into this phase of thinking about the Artemis missions and potentially sending humans to Mars. It is just so absolutely crucial that we have a better understanding of space weather for a million reasons. I can't even imagine how terrifying that would be, being out there without any warning.

Matina Gkioulidou: Yeah, because the ISS, the astronauts are still inside the Earth's magnetosphere, our protective bubble in our planetary magnetosphere. But once they get out there with Mars, no magnetosphere to protect them. Or on the way there, that all these particles are direct heats for those astronauts.

David McComas: Yeah, or even the moon. I mean, I do think that with the Artemis program-

Matina Gkioulidou: Or the moon, yeah.

David McComas: ... it's much more important now than it has been for decades that we really be on top of this real-time space weather, if we're going to have people routinely working on or around the moon.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, I wanted to get personal just for a little moment because David, I was reading more about you online and I think a lot of people are inspired by your story. You've talked a bit about how severe dyslexia has shaped your ability to visualize these complex systems in 3D. And I wanted to ask how those strengths have influenced the design philosophy behind IMAP and the other missions that you've worked on.

David McComas:

Sure, yeah. I'm pretty severely dyslexic, I didn't learn to read till fourth grade, and to this day I'm a very slow and bad reader, and don't ask me to spell anything. So, I still live with and I work with the limitations, the weaknesses that I have. But what I've learned is that I also have different strengths. I have very good spatial abilities to envision three-dimensional structures. I'm very good at taking big steps in connecting things that many other people don't see what the connections might be. And so, what I've learned over time is that dyslexia is a trade. There are some weaknesses, but there are also some strengths in it, and that's been to my advantage.

But more important than that, what I've really learned is that we're all different and different people have different strengths and weaknesses. And when you do something really hard and complicated like a space mission, you can't have everybody have the same strengths. You need a team that's really diverse in terms of their strengths, and they bring those strengths to the table. And if you have good leadership and you work together properly, everybody's working with their strengths and they're doing the parts that they can do better than the other folks in the team, and the team as a whole can achieve so much more that way.

And so, I think actually my journey with dyslexia taught me first and foremost that I didn't have to be a good reader to be really good at things that would play another important role in a project. And so, I think that's a really important lesson for us. And by the way, if people are interested in my dyslexic story, all they have to do is Google McComas and dyslexia, and I've talked about this at length in other forums.

Sarah Al-Ahmed:

I think it's so important for us to all understand that the things that some people might see as drawbacks are the things that can make us so special in other areas. Right? And everybody has those things that just makes them crucial to whatever thing that they're passionate about, right?

And also, this is a mission that just functionally is spread across so many different institutions. It's like 27 institutions with 82 partners across the United States and six separate nations have participated, right? And that's just a beautiful example of how each and every one of us can contribute to something together just with our own little specialty. Would you say that there are any surprises or rewards that have come out of this really kind of unique collaboration on this mission?

David McComas: Well, there are lots of rewards. I mean, we make tremendously good friends. I've got really good friends around the globe and across the country that I work very closely with, and we all succeed or fail together. And so succeeding together and having a launch and turning on all 10 instruments in space and having them all work fine and starting to get great science data, it's the success of now over 1,000 people who've worked on the project. Some of them aren't working on the project anymore, and some of the engineers and technicians once we launch, their job is over. But they're very aware of the science that we're getting and it's very important for them that the mission be successful in the science phase because at the end of the day, that's what we've all worked to do.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, the IMAP's nominal mission is about two to three years, but you designed it to last hopefully for much longer than that. If you can keep the spacecraft operating, say even for an entire solar cycle, what kind of science would that enable?

David McComas: So, that's the story from IBEX. I mean, IBEX, which was a small explorer, which was a very inexpensive, some people say that they use RadioShack parts. That's not actually true, but you certainly use parts which are lower quality than you do on a mission like IMAP. And we're in our 17th year of operation right now and cross-calibrating with IMAP. So, some of these missions can last a really a long time. And you look at how long the Voyager is still going on. So, if you can get a solar cycle or more of these observations, you're really able to fill in the three-dimensional structure of the heliosphere with a fourth dimension of time, and so you're then looking at the breathing-

Sarah Al-Ahmed: The breathing.

David McComas: ... of the heliosphere and it's time variability. We've already done that somewhat with IBEX. And what's really fun about having IBEX and IMAP together now for a little while, while we do cross-calibration hopefully over the next few years, is that we can tie this long time series of information that we have with lower resolution and lower sensitivity and higher background. So, not as good a measurements, but we're able to see this fourth dimension of time and then tie it into these really precise measurements that we're making with IMAP. The longer IMAP lasts and we're able to run it, the more we'll have those really precise measurements and the more deeply we'll be able to understand the solar cycle effects and the longer term effects as the heliosphere evolves and changes in time.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We said earlier that IMAP has an open data policy, at least after the point where you've already verified that the data is good. And for scientists and students that are listening to this right now who might want to get their hands on that data, what kinds of early data sets should we be looking out for?

David McComas:

I guess I'd start by saying everybody will be able to look at I-ALiRT data starting February 1st. So, if you want to see what the solar winds and energetic particles and magnetic field look like at IMAP 30, 40 minutes before they arrive at Earth, you'll be able to get online and look at that anytime you want.

Once we've validated the other data, we'll be making regular data releases and then the rest of the world can participate in the science of that. And by the way, we're hoping that when people do that, they'll contact us, because of course we're the experts on how the instruments really work and all of that sort of thing. We love to collaborate with people outside. In some sense, leading a mission, I end up paying for all of the work that goes on in the mission because I've got a cost cap that I promised NASA I'm not going to exceed and which I've stayed within during the development of the mission. When somebody comes from the outside and I'm not paying them but they're doing good science with IMAP data, it's like a double win for us.

Matina Gkioulidou: Yes.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Last question before I let you guys go. I've been thinking a lot more recently as we've been going through all of these very important anniversaries for so many different missions who have been out there for a long time, and including Voyager, which is going to be coming up on its one light day distance from Earth this next year, and ultimately its 50th anniversary. What do you hope people remember about this mission, say 20 or 30 years from now?

Matina Gkioulidou: From IMAP, that it was the mission that brought even more discoveries about the heliosphere, and that's what I hope. That it's the mission that will bring even more missions after that because we found things that are new and exciting and maybe we still cannot explain and we need this extra data point. I hope that's what it will bring, more excitement, more science, more discoveries.

David McComas: I guess for me, I'm hoping that people will think of this as maybe the first big integrated mission that put the science together from the pieces from the very start and did it with a really well coordinated team of people who worked well together and were able to do more collectively as a team than its individuals.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, good luck in the next month or so. You're going to be sharing some of your first images at conferences and waiting for it to get into its L1 halo orbit. So, it's going to be a very exciting time. And then all of the wonder of getting all of that stuff back. I know, Matina, in the past, you've talked about how you moved into instrumentation after having those experiences of getting data back from spacecraft. And so, I'm hoping that you have all that joy all over again now that you're getting to work on this new mission.

Matina Gkioulidou: Yes. I mean, I already got the excitement of building an instrument and testing it in the lab, as I wanted to do it firsthand. And now we get the data. It's very exciting. I don't know, it's amazing feeling.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, thank you so much for joining me and I hope to have you guys back when we learn more about this, because right now is just such an important time as we're in solar maximum. I think everyone in the space community is really thinking hard about what's going on with our sun and the interaction with us and just all the stars around us. This is such a beautiful mission, and we're going to learn so much from it. So, thank you for joining me.

David McComas: Well, thanks so much, Sarah. And of course we'd be delighted to come back and talk with you again in the future.

Sarah Al-Ahmed:

In this conversation and in last week's episode about Voyager, we've been talking about the heliosphere and how the sun shapes the space around us. Missions like IMAP can help us understand that invisible environment that protects earth and the rest of the solar system, but all of the science has very real consequences, especially as humans prepare to venture farther from earth than we have in decades. With Artemis II just around the corner, astronauts will return to deep space for the first time since the Apollo missions. So for What's Up, I want to bring in our Chief Scientist, Dr. Bruce Betts, to talk about what we knew about radiation during the Apollo era, and how astronauts were protected back then.

Hey, Bruce.

Bruce Betts: Hey, Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: So the past few weeks, we've been talking a lot about heliophysics and the boundary of where our sun interacts with interstellar space, but we also talked in this episode a lot about how local space weather can impact our planet and even astronauts someday. So, I feel like as we're on the cusp of going back to the moon with humans for the Artemis missions, wanted to ask how you're feeling about this upcoming mission. Are you excited?

Bruce Betts: I am excited, very excited. I'm concerned, but excited. They're doing something different, something exciting. So, here's best wishes for everyone involved.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah. I mean, anytime we send people to space, it's a dangerous scenario. There's a lot of unknowns in this situation. But as I was thinking about what we knew about space weather and things in the past when we first sent people to the moon during the Apollo missions, I realized that we didn't even do it during solar maximum. So, there's some extra things going on here.

Bruce Betts: Good call.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah. What was it that we knew about the radiation environment back during the Apollo era, and how did we protect the astronauts from it back then?

Bruce Betts:

Well, I can at least go into some of that. I mean, we knew about solar flares and the charged particles that come out of the sun as part of the solar wind, that there are the flares and associated things that pump out the particles will increase the amount and make it more dangerous.

And there was some level of shielding. I mean, you can't fly lead on a mission because of the density of the material, unless you have a different situation than they did. So, you had aluminum holes and things that would protect you against lower energy charged particles. So things like the Van Allen belts. So, there are different types of particles trying to attack you and your equipment in space, although I don't think they're doing it maliciously. You have the solar wind and things like mostly protons and light particles, light mass, low mass.

Then you got galactic cosmic rays, which are coming in from outside the solar system and tend to be heavier and put more of a punch into things, so they tend to pass through materials and pass into and sometimes through astronauts. So, I believe that's what they finally associated the little lights that astronauts would see in their eyes in the Apollo. So, several of the astronauts witnessed seeing little flashes of light, and apparently that, my impression is they settled on that was these galactic cosmic rays when they'd go through your eye and cause one type of weird physical response or another. I didn't get far enough to confirm, but I believe they saw a higher percentage of cataracts than you would expect in the Apollo astronauts, although it was such a small sample size.

But the other key point is they weren't out there very long. So, usually radiation damage to humans is a function of what the flux is of these bad things and then how long you're exposed to them. And they were out there for a few days. So, future missions down the road that they're thinking of with longer missions at the moon, near the moon will have more concerns, and so they're thinking about it.

Then just as a quick aside, you have missions that go, for example, to Jupiter and go to the inner moons and that is just a particle radiation nightmare because you've got these particles being spun around every 10 hours in the magnetic field of Jupiter and winging and slamming into things and resetting your computers and screwing up your memories. So, that's why it's been hard to get particularly Io and then why they've done so much work with Europa Clipper of shielding it as it goes past there, but they try to spend more time away from Jupiter.

Anyway, so what if we did something different right now, something we rarely do, which is a random space fact?

Automated: Rewind.

Bruce Betts: So this, we're talking moon. I went ahead and made non-random connection to the moon. There are about 100 missions that have been launched to the moon.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Whoa, that-

Bruce Betts: If you take all the countries, I mean, that includes the Apollo, the human missions, but mostly includes lots of robotic missions from a number of different agencies and countries, and a lot of failures, especially earlier in the program of the robotic things as we learned how to do things. So yeah, I started counting them up and realized, yeah, did a lot. I mean, that includes fly by orbiter, lander, human, the whole thing, but about 100 missions, which is not surprisingly other than Earth, the place most visited, and it does not have the highest travel rating on, I believe it's Planetary Trip Advisor, but it's not bad.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Went to the moon, not enough pizza, one star.

Bruce Betts: All right, everybody, go out there, look up in the night sky and think about the coolest thing you've either done or seen having to do with liquid nitrogen. The cool list. Thank you, and goodnight.

Sarah Al-Ahmed:

We've reached the end of this week's episode of Planetary Radio, but we'll be back next week with more space science and exploration.

If you love the show, you can get Planetary Radio T-shirts at planetary.org/shop, along with lots of other cool spacey merchandise. Help others discover the passion, beauty, and joy of space science and exploration by leaving a review or a rating on platforms like Apple Podcasts and Spotify. Your feedback not only brightens our day, but helps other curious minds find their place and space through Planetary Radio. You can also send us your space thoughts, questions, and poetry at our email, [email protected]. Or if you're a Planetary Society member, leave a comment in the Planetary Radio Space in our member community app.

Planetary Radio is produced by The Planetary Society in Pasadena, California, and is made possible by our members all over the world. You can join us at planetary.org/join. Mark Hilverda and Rae Paoletta are our Associate Producers. Casey Dreier is the host of our Monthly Space Policy Edition, and Mat Kaplan hosts our monthly Book Club Edition. Andrew Lucas is our Audio Editor. Josh Doyle composed our theme, which is arranged and performed by Pieter Schlosser. My name is Sarah Al-Ahmed, the host and producer of Planetary Radio. And until next week, ad astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth